Melodrama: Unrealised Potential – A game by David Cage

The humanity, or the surprising lack thereof, in a game about becoming human.

What is a little girl’s life worth? This is the first question Detroit: Become Human asks you, and it asks it again quite a number of times in quite a number of ways. That the game eventually undermines its own answer to this question in the third act is hardly even the eighth most disappointing part.

This was a game I had soaring expectations for. Maybe that was my fault. But I would be lying if I said the game did not factor into my desire to get a PlayStation 4. Sure, my decision was ultimately driven by games I ended up enjoying far more, like God of War, Horizon Zero Dawn, and Uncharted, but at one point, Detroit was a serious contender. So much so that it remains one of the two games I’ve ever pre-ordered (the other being Spider-Man – zero regrets there). Even with Detroit, there are no regrets; just…disappointment. And some resentment.

I had the game downloaded and ready at launch, and dove right in. I played a handful of the opening chapters and my enthusiasm just sort of fizzled out. I played and finished about seven other games – earning the platinum trophy on four – before I could bring myself back to Detroit. If that doesn’t seem like that many games, I’ve spent north of 130 hours on Horizon Zero Dawn. I took what was effectively a six-month sabbatical from Detroit, and returned mostly because of pre-order guilt. After I did, I made short work, finishing my first playthrough in a couple of days. Being the obsessive nut that I am, I played it again, and again, and again. All for that sweet, sweet plat. With four trophies to go, I couldn’t take it anymore. I toss in my sleep with the sure knowledge that I will one day compulsively play through it at least a couple more times.

Here is my largest problem with this video game: it’s not a video game. I don’t have a satisfactory answer to the question, “Well, what is it, then?” either. The best I can describe it is as a jigsaw of loosely connected cutscenes, in the middle of which you sometimes also press buttons. In all fairness, this is the first David Cage game I’ve ever played. For people who like the games he has made, I know I already sound like an imbecile that is utterly unqualified to have any sort of opinion on the matter. But I’m not trying to shit on a game that people enjoy. All I’m saying is that I was let down by a game that I so badly wanted to love.

From what I’ve read about David Cage, I see that he wants people to take video games seriously as an art form – to view it on par with more mainstream mediums like film or literature. There is nothing I would like more either. But emulating one or more of those established forms is not the way to go about it. Having gameplay is what makes a game a game. Sans that, I don’t understand what we’re trying to legitimise here.

Let me stop making vague disparaging remarks for a bit and make specific disparaging remarks.

The controls

They’re terrible.

Moving on to the story…no, seriously, the controls are horrible.

Control schemes, in general, are pretty uniform, and sometimes even game-agnostic. The left trigger aims, the right trigger shoots, X jumps and O dodges, rolls or evades. This is not true for all games of course, but within minutes of being introduced to all the possible moves and combinations, you can play a game confidently through to its end without needing a tutorial every five seconds. This is definitively true unless you’re getting back into a game that, for whatever reason, you put down last January.

Coming back to Detroit after half a year, I spent some time trying to reacquaint myself with everything, and there was decisively zero difference from all those months ago. I didn’t get any better now than I’d gotten then, because there is nothing to get better at.

The only interactivity in the game is in the form of arbitrary button prompts that need to be mashed before a very stressful timer runs out. Keep mashing X in a frenzy and you will miss the prompt changing, asking you to press O now once, and you will fail that prompt because you hadn’t stopped tapping X yet. Within minutes of starting the game, I decided that I would switch to the easier difficulty because I didn’t want to be hospitalised for a burst valve before I finished the game. I exaggerate. But only, not really. Every chapter has to end with a high-to-absurd stakes confrontation or chase or shootout or [insert any random Hollywood third act/climax cliché here].

What is the point of all these quicktime events? To test your reflexes? I just think that having a player learn a system of controls and then putting them in a situation that tests how well they employ what they’ve learnt is a far better way of doing it. It at least gives you a sense of accomplishment. If a game has to tell you what button to press up until the very credits roll, I feel like it has failed as a game.

I keep harping about this because it’s such a large part of the gripes I have with Detroit: Become Human. A uniform control scheme serves to ground me in the character I’m playing. Once it starts feeling familiar, I get into the skin of the role I’m playing, blurring the lines between the choices I make as a person in real life and the character I’m driving. I feel in control. Take for example, a session of Dungeons & Dragons. Its primary allure is the roleplaying involved. But imagine, in the shoes of your fantasy adventurer, if every time you set out on a grand quest, you need to be taught how to tie your laces over and over. Not only would that not be very entertaining, it would also get old faster than The Curious Case of Benjamin Button played in reverse at 4x.

But enough kvetching about the “action” sequences – which are just so much pointless melodrama. I don’t want the choices, conversations and dialogue trees to feel inadequately addressed.

Well, the UI is slick, I’ll give you that. But most of the conversation choices too have timers counting down, and there’s hardly enough time to take in all the options that you have. Maybe that’s just me, and my anxiety to not let the time run out. But there was nary a situation where I took stock of all my options, gave them the heft they deserved, and then made my choice. A cursory glance, and a quick tap of the button that seemed the least likely to antagonise everyone and most likely to keep my character alive was all I could manage.

There was a scene in the game where a supporting character, Hank, asks one of the androids you control, Connor, something along the lines of, “What kind of person do you think I am?”

The game promptly gave me a few options.

△ Sincere

O Cold

X Psychological

Or something very similar.

Now, like a damn fool, I assumed that each of those, when selected, were adjectives that Connor would use to describe Hank. How foolish of me. Turns out, those adjectives determined the nature of Connor’s response. Selecting sincere made him say something sincere – being a dick notwithstanding.

This sort of poor design permeates the entirety of the game. Off the top of my head, something as simple as making the buttons say: Reply sincerely, Answer coldly, Respond psychologically completely circumvents the issue. Granted, it’s not very flashy, nor will it fit in neat, tiny boxes, but it’s still better than me pressing a button, expecting to tell someone that I think they’re sincere, and end up telling them that I think they’re cowardly. Talk about a critically bad roll on a charisma check.

The controls make the game feel not unlike pressing random buttons on a television remote at specific times, and expecting the resulting channels to play something coherent.

The technicalities

The camera in this game nearly cost me a controller. The near-perfect, orbiting 3rd person cameras in games like God of War and Horizon Zero Dawn have perhaps spoiled me, but even if Detroit had been the first game I ever played in life, the camera would have still made me chuck things at a wall; most likely my head. The fiddly control, and the awful angles featured prominently in my growing frustration leading up to that initial “break” from the game. Yes, some set pieces, and some choreography were splendid when the camera pulled back and let the action do the talking – a scene where a few androids jump off a building comes to mind. But by and large, if I wanted to maintain such a psychotic grip on the camera, I would have opted for a fixed camera, and put in the work to frame things better.

For a first party game, Detroit could have used far more optimisation. It stuttered and fumbled noticeably in enough places on my PS4 Slim that I remembered it and found it worthy of mention. The television screens in the game were almost always playing consistently choppy footage. But by god, it’s a fantastic-looking game.

In many places, it’s a fantastic-sounding game too. I’m a sucker for orchestral, instrumental music, and it was the score that brought me closer to tears than anything else in the game. Though it can get just a little bullish at times, I found myself enjoying the swells and the sweeps thoroughly.

The writing

A game like Grand Theft Auto paints as ridiculous a premise as any. But by virtue of being a caricature, an over-the-top parody, it becomes a world so ludicrous, that we end up buying into it. The underlying, systemic flaw within the fiction of Detroit: Become Human is a woeful short-sightedness; an underwhelming vision and imagination. This is never a good comment to elicit, but it stings that much more when it has to be said of a work of science fiction.

In Detroit: Become Human, a game set in the year 2038, there is a magazine that has the headline: Cyberlife world’s first trillion dollar company.

In the real world, in 2018, the year that the game released, not one, but two companies already crossed the trillion-dollar market cap. While I realise how inane this nit I’m picking is, the writing is riddled with missteps and impossible-to-believe-things. It reeks of bad sci-fi. All the science mumbo jumbo, the talk of blue blood, and the whole android biology shtick sounded like the bad mysteries that I wrote when I was ten.

Science fiction is the genre that gets me to suspend my disbelief the quickest, because I’m so eager to believe, so quick to feel wonder. It’s no small feat that Detroit lost me right at the beginning.

The sub-par creative quality also extends to far more than just the science or the fiction.

To get a player to sympathise with a particular demographic of characters, if you have to alienate literally any other thing that so much as moves…I don’t know, it just seems like poor writing to me.

Every human in the game is a walking, talking cardboard cutout that has two settings: 1. Belligerent. 2. Psychopathic. I suppose the androids have Become Human™, and the humans have Become Assholes™. Written well, antagonists become people you love to hate. In Detroit, you can only roll your eyes and wish you were watching Scooby Doo instead; god knows there was far more nuance there.

I’ve never compared any game I’ve played to every other game I’ve played as much as I have Detroit. But that’s because it could have been so much more! In Horizon Zero Dawn, there are datapoints (that are in no way essential to complete the main storyline), that give the player information about laws that were passed to restrict the Turing level of any AI that humanity created. About activist groups fighting for the environment, for machines with high enough Turing levels, against a corporation making killer machines. About random pizza deliveries in the ancient past. They flesh out the atmosphere, make it wholesome, and make everyone appreciate the solid world-building.

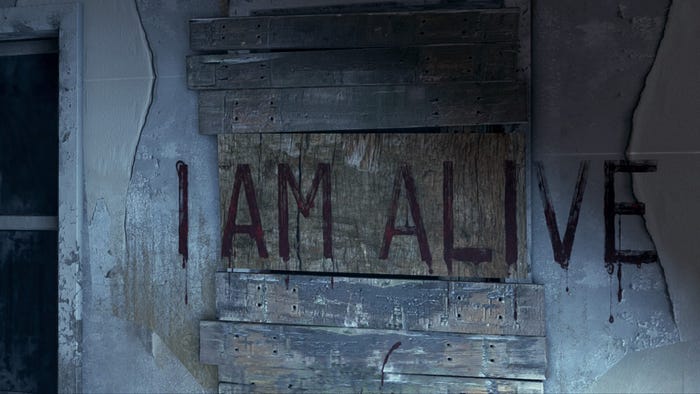

The nuggets in Detroit, however, are rarely even surface deep. Time and again the writing breaks immersion, and there’s no way to fix it. In essence, there’s no subtlety. The game does nothing whatsoever to “tackle” big, important, serious themes. There are random, unnecessary depictions of domestic violence that serve no purpose other than to underscore what boils down to the building block of the game: humans – bad, androids – good. Take the #BlackLivesMatter movement, replace the word ‘black’ with ‘android’, substitute sentient robots in place of African-Americans and that’s our game. Turns out, steeping a character in misery, just because, in an effort to evoke (some…any!) emotion does not equal depth. Who would have thought. Not only does it fall flat, it’s also transparent. It’s not poignant. It’s not even fun (I can name at least one excellent game, that isn’t, even in the loosest sense of the word, ‘fun’. The Last of Us, in case you were wondering). It’s a massive pile of nothing.

I can’t very well talk about writing without talking about the story, can I? Here’s the thing. It’s not very good. I have no problem with pulpy stories, chock full of tropes, that run the cliché boat into the ground. Uncharted games were textbook pulp, but they had genuinely fun gameplay to go with it. I maintain that Spider-Man PS4 is the best movie Marvel never made. I just think that if you want to make a cinematic, blockbuster of a game, there are better ways than the one that David Cage chose for Detroit.

During an interlude, a character called Amanda says to Connor, “Connor, would you mind a walk?” Does that sound like how human beings talk? I know how hard it is to write good dialogue, but it doesn’t take too much to make it not awful.

In some conversations, particularly while playing as Connor, certain speech options suddenly make him a livid prick, completely out of touch with how I was choosing to play him.

The branching narratives, the selling point of the game, are a lot like a buffalo’s bollocks. I’m sure they exist, but I don’t imagine I’ll ever see them up close. Even if I did, it probably wouldn’t be very pleasant. All the characters you control can die at any point in the game. But that largely means nothing at all, because the game will go on much the same. This verges on spoiler territory, but one of the androids has specific points in the game where you can die multiple times. In the same playthrough. So that’s a hoot. Deaths essentially have no bearing on the overarching plot. Neither do the majority of your choices. However, in very rare instances, spare or choose to save a character and they might make an appearance later in the game for a little deus ex machina; that was pretty neat.

When it comes down to it, if I had to describe the experience of playing Detroit: Become Human in one word, that word would be: tedious.

The conclusion

It prickles me to no end that the world does absolutely nothing to react to you. Even if you’re a random android standing around somewhere you clearly don’t belong, eavesdropping on conversations between strangers in plain sight, no one bats an eyelid, or so much as gives you a second glance.

The game feels static and lifeless, and it manages to do so by shackling the player with remarkably limited agency. For a game about player choice, this seems like a marvellous achievement. In a cleverer game, the world could have been made an excellent meta-narrative, a metaphor for the life and vibrance of the robots in the context of their existence alongside the humans that don’t appreciate them, that resent and loathe them even. The graphics are stunning, no doubt; the visuals, spectacular. But the reality that those visuals render, well, it’s just thoroughly disappointing.

And while on the subject of a cleverer game, how cool would it have been, if deviancy in the androids you control meant that they would start reacting unpredictably to player “commands” once they become deviant?

Sadly, this is not a cleverer game. It’s not even a cle game. If you remember, it’s not even a game.

I’m so hard on Detroit because it had the potential to be one of the best games I’ve ever played – almost all of which goes un– or under-realised.

Detroit: Become Human is fundamentally a deeply flawed game. The argument could be made that humans are fundamentally deeply flawed, and thus the game functions as an excellent simile to our own humanity. It just wouldn’t be a very good argument.

Until such a time when David Cage decides to make actual video games, I’ll be here with my novel written entirely in YouTube links and my movie that’s 12 hours of text scrolling past.